MerMEED Project (2015 - 2020)

Summary

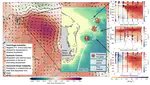

Over the last decades, oceanographers have been searching for the missing mixing in the ocean to complete the ocean energy budget. Answering questions of where energy is added to the oceans, and where it is removed, helps us to understand the drivers of ocean circulation. With the advent of high-resolution satellite measurements of surface currents in the 1990s, scientists could see that the oceans were filled with swirling vortices of water called mesoscale eddies. While eddies are present in all ocean basins, with currents inside the eddies sometimes exceeding 1 m/s, they disappear from satellite measurements preferentially at western boundaries. There are several possibilities for why eddies disappear at western boundaries: they may radiate energy away, contribute energy to large scale ocean circulation, or lose energy locally through turbulence and dissipation. Of these candidate terms, previous work has suggested that local dissipation is strong enough to explain a substantial part of the eddy disappearance. Our aim is to determine how and why eddies are losing energy at the western boundaries. These results and our measurements will then be made available to scientists involved in numerical simulations of the ocean. As a longer-term goal, the results of our research may help guide how eddies are represented in ocean models, which is one of the critical areas needing improvement in climate simulations. However, due to the fledgling nature of the science in this field, that eventual goal is still several steps away.

Fundamental physics dictate that most eddies move slowly westward, and these eddies are visible in satellite measurements of sea surface height a few months before they arrive at the boundary. In the project MeRMEED, we will watch the eddies in near real-time satellite data, and when an appropriate eddy approaches the east coast of North America, we will deploy a small team of researchers, with advanced instruments, to meet the eddy upon arrival. There, we will survey the eddy using high-resolution profilers deployed from small boats and autonomous underwater vehicles called Seagliders. After the ship-based survey is completed, the gliders will continue to observe the eddies for several months, as the eddies are slowly disappearing. These gliders transmit their measurements via satellite communications back to our base station in England. We also plan to use the existing observations from the joint UK/US-funded RAPID programme, measuring ocean circulation at 26N. We will install additional high-resolution velocity and temperature meters on one of these moorings, to make continuous observations of the eddies over 18 months. From the survey, glider and moored measurements, we will be able to assess how important local dissipation is to the disappearance of eddies. We will use our findings to shed light on the processes responsible for eddy disappearance from the oceans, and how those processes change in time.

NERC Reference: NE/N001745/1, NE/N001745/2, NE/N001745/3

Data

There are three main observational data streams for MerMEED.

- Additional instruments (thermistors and two 75 kHz ADCPs) were added to one of the RAPID project moorings in 1400 m of water east of the Bahamas, to make high time resolution (10s sampling on the thermistors) and high vertical resolution (every 50 m for thermistors, 16 m bins for the ADCPs) measurements at the edge of the continental slope where the eddies encounter topography. These were deployed in autumn 2015 and will be recovered in winter 2018.

- Very small scale measurements of ocean velocities and temperature are made in the top 1000m of the water, near topography, by at tethered microstructure profiler. These specialised instruments will make direct estimates of dissipation in the eddies

- Autonomous underwater vehicles (Seagliders) make multi-month observations of temperature and salinity in the top 1000 m. These observations will give a detailed look at the changes in the subsurface structure of the eddy as it encounters topography. They can additionally be used to estimate turbulent dissipation through methods that are still under development. Together, these observations span the space- and timescales of mesoscale eddies down to 10-cm scale turbulent vortices in the water, to enable us to better understand the processes by which eddies lose their energy when they encounter topography.