Deep convection in the Labrador Sea

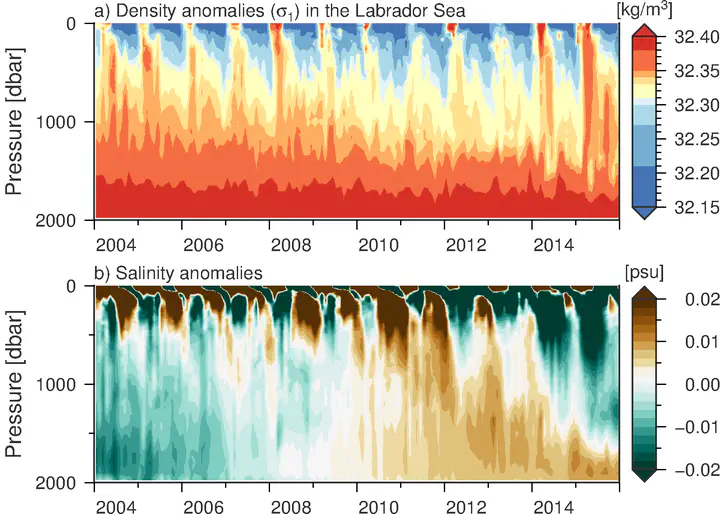

(a) Density and (b) salinity anomalies in the Labrador Sea given by Argo float data. In 2013/14 and 2014/15 convection was deep, while the Labrador Sea Water produced was relatively fresh.

(a) Density and (b) salinity anomalies in the Labrador Sea given by Argo float data. In 2013/14 and 2014/15 convection was deep, while the Labrador Sea Water produced was relatively fresh.In the wintertime in the Labrador Sea, eastward travelling cold dry air from the Canadian Arctic archipelago and storms from northeast American encounter their first bit of ocean over the subpolar North Atlantic. Ocean sea surface temperatures in this region are warmer than the surface temperatures over land since they can’t remain below -1 degrees for long. This means that the ocean is warm relative to the atmosphere, and so gives off heat to the atmosphere which cools the surface waters. When waters become cooler, they become denser; if they get denser than the waters beneath them, they sink, mixing with deeper water. This process is called “deep convection”, and the end result is a well-mixed deep water mass. There are only a few places in the world where deep convection can occur in the open ocean (as opposed to continental shelves or marginal seas), including the Labrador Sea (between Canada and Greenland), Irminger Sea (between Greenland and Iceland).

Year-to-year there are a lot of variations in the intensity of convection, as measured by the volume of deep water created (volume of water of about the same temperature and salinity), thickness of that deep water mass, depth of the deeper edge, or density of the deep water. For the recent decade, convection was relatively weak in the Labrador Sea, with the depth of mixing typically confined to the top 1000 m. But in 2013/14 and 2014/15 winters, convective depths exceeded 1500 m and the outcome can be seen in these time-depth plots of temperature and salinity.

In the figure, you can see a clear annual cycle in water density in the Labrador Sea. Water is denser in the wintertime, and lighter in the summer (blue). Just after the 2014 tick mark and the 2015 tick mark, the vertical stripe of red indicating dense water reaches from the surface to 1500 m indicating deep convection (after 2009-2013 having only oranges and yellows denoting less dense water). This signals the return of deep convection, particularly in around February and March 2015.

At the same time, the salinity of those dense waters has been decreasing (freshening) shown in the lower panel. This contradicts some of our expectations about convection - that in extreme cases, with a large input of freshwater to the region, even large heat loss in the wintertime would not be able to create dense enough water to sink. In TERIFIC, we will take a closer look at the process of deep convection and how buoyancy is transferred between the ocean and atmosphere.